|

|

|

Presentation

"We are Amused"

Victorian Humour in the Digital Age

7-8 November 2024

Maison de la Recherche (MRSH)

Université de Caen Normandie, France

This hybrid conference aims to examine the intersections between nineteenth-century humour, under all its definitions and expressions, and the digital. In line with the ongoing Punch’s Pocket Book Archive project (please follow our new project blog here), which will ultimately create a fully searchable, open-access archive from a complete collection of Punch’s Pocket Book – some thirty-nine volumes representing approximately 5,000 pages – the conference will investigate the migration of jokes, squibs, spoofs and parodies, verbal and visual, from the pages of comic periodicals to 21st century screens, opening new lines of inquiry into the distinctiveness of computerized Victorian humour.

In his 2022 Michael Wolff Lecture entitled “Limits and Limitlessness: Miscellaneous Extraction in Nineteenth-Century Print,” Mark Turner remarked that “the digital age does not signal a break with earlier dynamics of print modernity. It represents the diffusion, extension and automation of logics, techniques and concepts that emerged across the nineteenth century” (Turner: “Limits”). Far from merely displaying scanned pages on a screen, digitization does indeed raise central questions about the rationale behind the decisions made by the authors, editors, publishers, proprietors, illustrators, engravers and readers who, throughout the nineteenth century, constructed, circulated and consumed the printed press. As they sit today on the shelves of libraries, as bound volumes or in the shape of microfilms, Victorian newspapers and periodicals testify to the immense variety of features, contents, types, illustrations and formats that resulted from such decisions. They also bear witness to the work of archivists who, since then, have decided to save a collection, or else to dispose of it, thereby broadening or narrowing the range of resources historians of the press can engage with today. As James Mussell puts it, “the archive is an interpretation in its own right and then every time people return to the archive and do things in it, every return leads to new ideas and new ways of conceiving the past” (Brake & Mussell: “Digital Nineteenth-Century Serials”). As yet another return to the archive, the creation of a new digital repository is thus a bibliographic process which, relying on a thorough analysis of the source material, inevitably transforms our perception, understanding and rendering of it.

Over the last thirty years or so, the range of Victorian newspapers and magazines available for data mining and content analysis has remarkably expanded. Impressive platforms like the Wellesley Index, Waterloo Directories, British Newspaper Archive, Nineteenth-Century Serials Edition, Illustration Archive, Yellow Nineties, Digital Victorian Periodical Poetry have fundamentally altered the way researchers approach the archive. It is however estimated that less than 1% of surviving nineteenth-century newspapers – themselves a fraction of printed papers – have been digitized (Brake & Mussell: ibid., Joshi: “Scissors-and-Paste”). Among the print genres covered by these repositories but still insufficiently available online is the multifarious, ebullient and highly entertaining nineteenth-century satirical press. As the most influential humorous title of the period, Punch was digitized in 2014 under the supervision of Clare Horrocks and Seth Cayley, in conjunction with Gale Cengage and the British Library. Today,the Curran Index provides listings and author attributions of 80,161Punch articles covering the period 1842-1900. But while the London Charivari remains to this day a household name for Victorian satire, the magazine was far from being the only entertaining publication on the market. Largely inherited from the Regency tradition of popular comic art, and fuelled by the exponential development of the pictorial press throughout the 1830s and 1840s, as Brian Maidment has convincingly documented, a new “middlebrow” consumer market for visual culture provided the early Victorian reading public with an abundance of comicalities (Maidment: 3). Every day, comic stories, songs and poetry brought a smile on the face of a public posterity has chiefly described as dour and repressed. As more recent Victorian historiography has shown, fun was omnipresent, on paper and in people’s lives. Jokes, Bob Nicholson has observed, “acted as a literal form of capital; a conversational currency that could be exchanged for a good evening of food and drink” (Nicholson: 123). They could be found in almost every kind of publication, but particularly flourished in “comic periodicals,” a print genre Donald Gray defined in one of his founding articles on the subject as a cheap illustrated weekly, with half-page caricatures and small punning cuts (Gray: 2). Of these playful publications, Gray lists no fewer than 200 for the whole nineteenth century, observing that many of them were issued during the middle decades, as Punch imitators. Among these titles, only a handful are freely available online. While The Tomahawk (1867-1870) can be viewed through the Nineteenth-Century Serials Edition, a free, online scholarly edition of six nineteenth-century periodicals and newspapers, other titles remain either behind paywalls (Bell’s Life in London, Figaro in London, Fun, Judy) or are still trapped in what Patrick Leary has famously called the “offline penumbra” (Will O’The Wisp, Moonshine and hundreds of others) (Leary: 82).

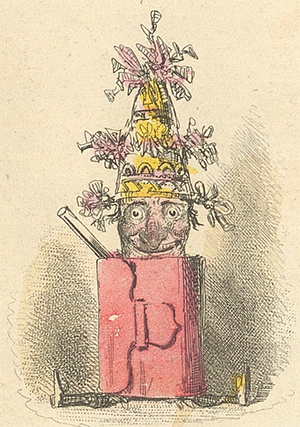

Jocularity also pervaded more transitory and elusive texts like pocketbooks, almanacs, diaries, posters and tickets, overwhelmingly absent from library shelves and computer screens because often dismissed as insignificant. Among such journalistic outgrowths was Punch’s Pocket Book (1843-1881), a “cheery little annual” launched by Bradbury & Evans to support the fledgling Punch (Burnand: 168). Inspired by the weekly magazine’s mixture of jokes and cartoons, it offered serious and trivial content, interspersed with black-and-white vignettes and ornaments. Its main selling point was a hand-coloured fold-out frontispiece offering amusing comment on a topical issue. Today selected for digitization through an international project scheduled to unfold over the next five years, Punch’s Pocket Book raises fundamental questions about the impact of the digital migration on our perception, understanding and transmission of Victorian humour, visual and verbal. How might we better catch and display such formats and contents? What sort of taxonomy will better counter the “tyranny of the keyword,” which, in the words of Harry G. Cocks and Matthew Rubery, will “parachute us in the middle of a print jungle and ignore the nature of the ecosystem”? (Cocks & Rubery: 1)